Now I can tell

where y’all have been*

Jam+from+Mexico%22&meta=

Take a look at yourself. You are responding to a reflex in speaking with your search engine. It is a mixture of hunting instinct and stuttering. You revert to the early days of language acquisition. No longer do you think in full sentences, but rather search for a decisive word of condensed desires. In your semi-conscious, outcome-oriented haste, you use meaningless formulations, transforming complicated wishes, hopes and desires into keyword entries. In no way adherent to a guaranteed system, these entries constitute a mere echo of your statistical speculations on internet conventions. You make an entry in the search box in the net lingo. You follow your expectations of that single word, a word distinguishing your goal from all that is on offer. Perhaps all of a sudden you remember your yearning for a more steadfast love and enter the words ➚ going to stay forever on Google.

How might the engine answer you? On June 9, 2003, the list of results was headed by a discussion contribution on sanctions in Iraq, followed by New Zealand’s reflections on the anti-ageing effects of nanotechnology and, in third place, strategies for the re-education of internet itinerants as automaton-like consumers. One could assume that you may perhaps be disappointed. In the top spots of its result pages, Google offers you no instructions at all for emotional stability, instead reinterpreting your yearning within technocratic contexts. Yet did you really want to find anything? You could also have gone to Google with the question ➚ will things continue like this? Anyone posing a question like that can hardly expect solutions. Rather he or she is engaged in an oracular dialogue, for which the proffered information on training methods for World Cup skiing or the Financial Times recommendation for precarious market developments are abstract additions. The search engine is your conversation with yourself. Of course you could type in ➚ Old Assyrian marriage contract and be able to archive 16 advocatory answers, but that is an unusual case. If you read the running entries made by other users on the search engine’s live pages [no longer available], which read like a news tickertape from the collective sub-conscious, you can feel the beat of sudden impulses becoming categories: MOTOR SENSE, TAMPON GIRL, CHIEF APOSTLE FEHR, EROFILI BEACH HOTEL, STONEWARE PIPE, DRIVER’S LICENCE WITHDRAWAL, DEAD MAN IN THE TENT? What tent? Does it depend on the answers?

The linguistic echo of desires develops its own autonomy. One might interpret it as the beginnings of a spontaneous artistic obstinacy when the microbiologist asks his computer: ?hl=de&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&q=Do+I+really+want+it%3F&meta and the computer answers, entirely by random, »What will it cost me?« Anyone making conversation with Google won’t be writing a text as such, but rather concocting a linguistic concentrate of his or her desires, as if seeking to articulate a declaration of love on a multiple choice form. It is quite possible that ➚ speaking in the 1st person calls for a piece of grammatical advice (or a research course). One suspects which essentially modest fetish the sender of ➚ naked women in monster trucks is looking to gratify. Google is the world ranking list of a stock of information in which not only personal desires are sounded out, but also publishing academics and exhibiting artists regularly search for themselves, attempting to find a reflection of their existence in the quantity of search results. Google is not fictitious. Google is a market, an arena with touchline advertising and licensing revenue. In the world of the internet, it is a sovereign institution. Yet the search words entered by users are not Google. They are moments in which language submits to a machine, to instinct and to the prospect of a primitive encyclopaedic order. Google is a world-encompassing ➚ fantasy of omnipotence.

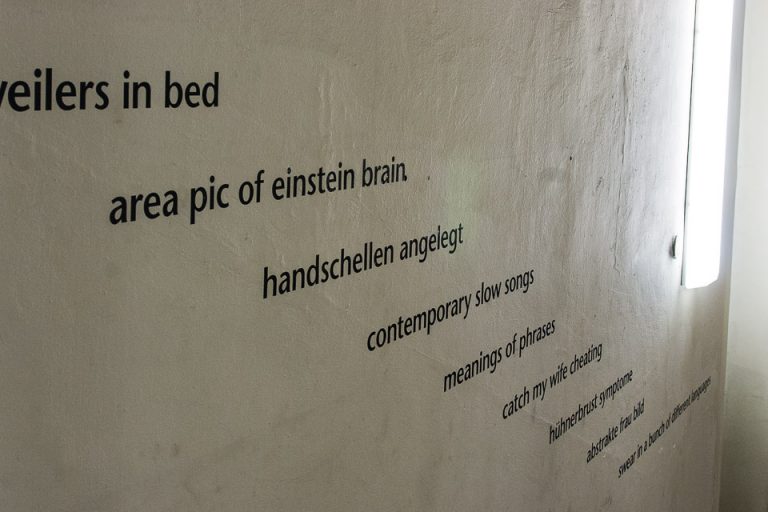

So what is it that Adib Fricke has installed in the stairwell of the Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene in the Medical Faculty of the Humboldt University, Berlin, by applying a series of anonymous search items step by step to the plaster? The opposition of duration and spontaneity? A symbol of information-technological uniformity? Ready-made poetry? Peinture automatique?

More than being about all this, it is a work about words which, devoid of all contexts and communicative intentions, commence a functional life of their own, latently absurd, ciphers of a mechanical process. Fricke has spent time reading the live search pages on the internet, which are updated every ten seconds, helping himself to the content of strangers’ logfiles**. He has posted web pages on the net as bait and gone on to evaluate the data of visits to the various pages. This is how a group of signs evolved, never growing beyond their status as search words, yet maintaining sufficient autonomy so as not to be entirely absorbed by the artistic installation, whereby they become part of an abstract pattern in a stairwell. Fricke is an expert with signs such as these. He runs The Word Company (TWC), which produces protonyms, meaningless made-up words, presenting them with all the means available to marketing as a universal solution. The ironic market crying, with which his websites draw deliberately meaningless signs such as ➚ SWOKS, ➚ ONOMONO or ➚ RIMITOM to the public’s attention, equates their subsequent painterly processing with Nike®, Persil® or Canon®. Art is situated in close proximity to product advertising, all the while inventively countering this very phenomenon, albeit with ever-precarious boundaries. It is a practice balanced between marketing, self-promotion and a defiantly ironic peculiarity.

This is precisely what we encounter in the search words exhibited in the Charité. Fulfilling all the requirements of an artistic installation with decency, they scatter allusions, questions and references and emit linguistic echoes of the search activity. Besides reminding us that research is always grounded in language, that it is often a miracle of non-linguistic desire, Fricke’s artistic intervention continually withdraws itself from its professional art consciousness, thereby returning to the status of an instrumental desiring machine stutter which the artist has taken on board wholesale. Such is the capacity of art. And thus it can fall back into its own context at any time. And the accompanying sceptical criticism levelled by art at itself is nothing to be sneezed at. What we witness in the research institute is art suddenly demonstrating precisely that which is all too often said about it: a degree of self-reflection worthy of imitation coupled with a view towards the outside world.

**) Logfiles are protocol registers set up by servers to count and record visits to a web site. They also contain so-called “referrers”, which are references to the previous sites visited by users prior to their arriving at the current site. Among other things, these files make it possible to ascertain the search words via which users arrive at a particular result page. Adib Fricke not only collected such referrers on his own server, but also searched on foreign servers with negligent security

Text from the catalogue “Jam from Mexico”.

© 2003 Gerrit Gohlke and Adib Fricke, translation (from German): Catherine Nichols.